Victoria Cave goes virtual

A London-based digital archaeology company, DigVentures Ltd., thanks to an award of £100,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund, have successfully digitised the Victoria Cave archive. Objects in the collection dating back over 600,000 years range from the remains of Palaeolithic fauna such as hyaena, elephant, rhinoceros and Cave Bear (Ursus arctos) to Upper Palaeolithic implements and Romano-British jewellery. The ‘Under the Uplands’ project ended in December 2016 and also included material from the previously unexcavated cave site of Haggs Brow Cave, also near Settle.

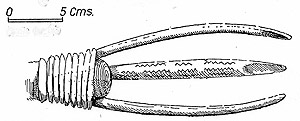

Victoria Cave: bone fish lance (Upper Palaeolithic 10,991±203 BC)

Working closely with Tom Lord, the holder of the archive, the company has created 3D digital models of all of the artefacts in the archive, as well as a 3D model of the caves’ interiors. This will allow anyone with access to the technology – on a computer, mobile phone or similar device – to view the entire collection at the touch of a button and navigate their way around it object by object, without having to visit or handle the physical archive directly, as well as experience the cave environment.

As Lisa Westcott Wilkins, DigVentures’ Managing Director, says, this will put “the entire collection in everyone’s pocket.” The creation of what is in effect a virtual museum it is hoped will tie in with the latest communication and presentation technology, enabling cave archaeology to enter the digital age and reach a much wider and more diverse audience than traditional methods of communication such as journals, lectures and museum exhibitions could ever do.